Earlier this week, I popped into Bangkok on my way home from Australia, to present to the Thailand Guitar Society about focal dystonia, and my approach to its resolution. Getting the chance to speak to guitarists and guitar teachers about this issue which has been popping up with increasing frequency around the world in recent years was a wonderful way to end a month of lovely experiences; my thanks to the Thailand Guitar Society and the Asian Guitar Federation – and in particular, Dr Paul Cesarczyk, Khun Sira Tindukasiri, and Ms Veda Aggarwal – for making it possible for me to share what I know. Below is a synopsis of my presentation.

To begin with, let me take a couple of minutes to tell you a little about dystonia in general. This is not immediately pertinent to focal hand dystonia as we know it in the context of the classical guitar, but I think a basic awareness of the issue might be helpful for context.

Dystonia, in essence, is characterised by abnormal, involuntary, and in some way disruptive flexion of one or more muscles or muscle groups. It can happen to a number of parts of the body, arise for a number of reasons, and have varying effects on the functional abilities of an affected person. As such, ‘dystonia’ itself is an umbrella term that covers a wide range of problems. The most commonly known forms of dystonia are generalised dystonia, and focal dystonia. Additionally, especially in recent years, some forms of dystonia have been known to arise as an adverse reaction to various drugs.

Generalised dystonia, though not pertinent to musicians for the most part, is the more commonly addressed form of dystonia in health and medicine. As the name suggests, it generalises across the body, often starting in one limb, and creeping over time to affect larger portions of the body. Often, this ends up disabling a person in the most basic of ways, such as walking or running. An example of this kind of dystonia is runner’s dystonia. A simple search for generalised dystonia on youtube will give you a number of very disturbing videos of otherwise perfectly healthy people, whose legs clench up and contort themselves in rather painful-looking ways when they try to walk.

Focal dystonia, which is much more pertinent to our context, differs from generalised dystonia in the sense that the dystonic tendency – the involuntary cramping of one or more muscles – is focalised to one body part. It doesn’t spread across the body – thankfully, I suppose – but is debilitating in that it can interfere with or completely shut down a person’s ability to perform one or more tasks. Non-musical examples of common focal dystonias are cervical dystonia (which manifests as a twitching of the neck one way or the other) and blepharospasm (rapid involuntary blinking), which most of us have probably seen in someone at some time in our lives. Musicians who experience dystonia typically experience focal dystonia, but with the difference that whereas other focal dystonias – like cervical dystonia and blepharospasm – are often non-task-specific, musician’s focal dystonia is commonly task specific, and tends to occur in the body part that is most important for musical performance. So, for example, guitarists, pianists, and other chordophone players tend to experience focal dystonia in one or the other hand, whereas wind instrument players tend to experience it in the muscles surrounding their mouth (embouchure dystonia). Drummers, for the same reason, have been known to contract focal dystonia in either of their hands or feet. In most of these cases, the affected person is perfectly functional in most aspects of their life, except when they try to play their instruments. Classical guitarists with focal dystonia, for example, are often able to type, drive, shuffle cards etc, and only experience dystonic symptoms when they play the guitar.

Recent research has shown that musician’s focal dystonia tends to be localised in whichever body part is involved in highly repetitive interactions of gross motor strength and fine motor coordination. In classical guitarists, that tends to be the right hand. For the rest of this talk, for our purposes, I’m going to speak of ‘dystonia’ or ‘focal dystonia’ in the context of how classical guitarists experience it most often, i.e., with task-specificity and in the right hand. As we move along, I’ll tell you how dystonia as classical guitarists experience it is not a disease or a disorder in the most commonly understood sense of those terms, but something that can be ‘learnt’, and equally, unlearnt.

To give you a sense of what a classical guitarist’s dystonia looks like, take a look at this video. This guitarist is experiencing focal dystonia in his a finger. For the purposes of illustration, the involuntary clenching of his a finger is most clearly visible from 00:55-01:30.

Before we go any further, and now that I have shown you what dystonia might look like in a classical guitarist, let’s step sideways for a moment and go over a very brief and basic psychology lesson. This will help with understanding how dystonia for classical guitarists develops, functions, and can be resolved.

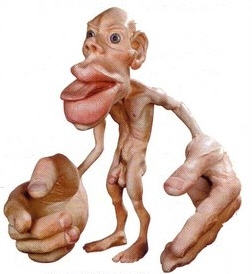

Any voluntary act, including playing, is an outcome of neural activity in the brain. Neurons fire in parts of the brain that control the movement of particular body parts, and muscles contract and relax as a result. This activity takes place in a part of the brain called the somatosensory cortex. Control centres for each part of the body take up specific areas within the somatosensory cortex – or each part of the body is ‘represented’ on the somatosensory cortex. This representation of the body is called a homunculus representation, and fine motor functions, such as fretting and plucking strings, are possible because of it. A homunculus representation is key to our ability to perform precise and delicate actions, because it means that the parts of our bodies that require the most control from the brain are allocated more space within the somatosensory cortex. You might have come across this popular representation of a homunculus, which tells you what we’d look like if our bodies were built the way they’re normally represented in the somatosensory cortex. You see that it’s really all about the hands, the mouth, the face, and in comparison the rest of the body is controlled with very little brain power.

In the context of voluntary movements, neural activity serves two purposes or processes – activation and inhibition. Activation is easy. It refers to muscles, and groups of muscles, contracting. Clenching your fist is a very basic example of hand activation – even babies with their grabbing reflex are experts at it. Inhibition, on the other hand, is complicated. Really, for the most part when we as guitarists talk about developing our hands for better finger separation, we’re talking about our brains getting better at inhibition.

Our brains learn – get better – at inhibition, and thereby at controlling and enabling fine motor movements like virtuosic playing, through a process or a tendency called neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity essentially means that your brain is ‘plastic’, or changeable. It changes to become more efficient, in response to the tasks you require it to perform repeatedly. Repetition is key in this. Being efficient, the brain doesn’t waste time changing itself for every random function you ask of it – it only changes when it ‘sees’ from experience that some complex task is likely to be asked of it repeatedly.

Two processes direct the way the brain changes itself in response to one’s activities. One is the process of repetition itself. The areas that represent the appropriate fingers on the somatosensory cortex of a guitarist playing a tremolo, for example, fire repeatedly through p-a-m-i (or whatever other variation you might use to play a tremolo, of course). As the saying goes, practice makes perfect, and when tasked with repeatedly enabling you to move through p-a-m-i, the brain adapts by reinforcing the connections that make that sequence of neurons firing easier and better. The other process that guides neuroplasticity is sensory feedback, or perception. The brain, as it fires through p-a-m-i, also constantly processes the sensations your fingers register as they play. The qualitative nature of this second process – sensory feedback – is key in the brain adapting correctly to help a guitarist play better. That is, when sensory feedback is accurate, and congruent with the brain’s experience of a repetitive task, the brain will adapt to facilitate virtuosity. However, if there is a repetitive discrepancy between a given pattern of neural activity (brain cells firing in the somatosensory cortex), and sensory feedback, the guitarist’s brain’s tendency to change to adapt to the task it sees as regular, and worth getting better at, can take a wrong turn, resulting in focal dystonia. Altenmuller et al have illustrated this via MEG scan, where the representational areas of a musician’s dystonic hand are blurred on the somatosensory cortex, in contrast to those of a non-dystonic hand, which are not. In the context of guitarists, this can happen when our perceptions of our own highly repetitive complex right hand actions (think of some Giuliani or Barrios passages) are incorrect, and don’t actually conform to what our brains are doing to play those notes in the first place.

So that, basically, is how dystonia typically arises in classical guitarists. Of course, it is important to remember that the process I have described does not happen a lot more often than it does, because most musicians in the world don’t have dystonia (even though the number that do is significant enough for us to be talking about it today). In fact, reported rates worldwide tell us that about 1% of all classical musicians develop focal dystonia. Some factors that have been found to predispose a given musician to contracting dystonia are:

- Long spells of virtuosic practice. This is the number one contributing factor. Long hours spent playing loud and fast are more likely to predispose one to developing dystonia than anything else. This is particularly true when one is practicing passages that involve more than two fingers on the right hand moving rapidly in repetitive patterns.

- Age – most dystonic musicians are aged mid-20s to mid-40s when they develop it.

- Men are more likely to develop it than women.

- There is a genetic component to the extent that anyone is predisposed to developing it.

- A sudden increase in the amount and intensity of practice, as one often sees musicians doing before an exam, competition, or audition.

- Personality type – type A personalities and perfectionists are more likely to develop dystonia than other personality types.

- The age at which one started playing – people who begin learning an instrument after the age of 9 are 6 times more likely to develop focal dystonia than people who start learning at a younger age. Just going by the particular demands of playing guitar, and how many people consider younger children unable to start learning the instrument until their hands grow a bit, I’d say that puts guitarists especially at risk!

From that list of factors that predispose one towards developing focal dystonia, one might well say that classical musicians are at significantly higher risk for developing dystonia than other people – and the research bears that out as well. Eckart Altenmuller, whom I mentioned earlier, found that professional classical musicians are 800 times more likely to develop focal dystonia than other people. Another recent study (Rozanski et al, 2015) made a recommendation to the German Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, and in fact, in Germany, musician’s focal dystonia is now recognized as an occupational disease, and professional musicians who develop it in Germany may get support for their treatment.

So with all of this said, how does one go about resolving focal dystonia? I do have my own approach, which I’ll share in a moment, but because a) different people respond differently to different approaches, and b) even the approaches that don’t work in isolation do help as priming or coping strategies when incorporated into other approaches, here’s a list of what’s out there:

- Emotional therapy/counselling – of the sort that is most identified with Dr Joaquin Fabra. In my experience, working on the emotional component of dystonia is not ultimately effective for guitarists, but it does help with laying the groundwork for another, more effective approach. This may be because it often helps the affected guitarist take the first step towards resolving dystonia, which is coping with any anxiety and stress issues that arise as a result of having focal dystonia – as you can imagine, not being able to play for reasons you don’t fully understand would give rise to considerable anxiety and stress, which in turn do get in the way of a dystonic musician applying himself or herself to a program aimed at resolving their dystonia.

- Botox injections – going back to our initial understanding of dystonia, recall that dystonia is characterised by unwanted contractions of particular muscles. Botox injections directly into these muscles inhibits their functioning. Yes, it is as drastic and unsustainable as it sounds, and I am not an advocate of this approach. I believe that there is a bit of a problem with over-medicalization of musician’s focal hand dystonia – especially considering there is no pathology involved in the condition – and botox treatments are a part of that.

- Retraining or developing alternative technique – various people have come up with alternative playing techniques to get around the problems posed by a dystonic hand. I don’t personally know of any cases of success through this route, other than David Leisner, but they are out there, so I’m mentioning the option.

- Slow-Down Exercises (SDE) – a pedagogy-based approach that proposes that dystonic tendencies have a temporal threshold, and that retraining can be done by playing under that threshold (very slowly, as with exaggerated slow practice), and that this threshold can gradually be raised to facilitate normal playing. I have not personally found this to be effective, but its principal proponent, Dr Naotaka Sakai, has apparently helped a number of pianists resolve focal dystonia and return to the stage.

- Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) – brain surgery, which is as drastic as it sounds. There are obviously major concerns associated with this approach, which is more often used to address other, more serious forms of dystonia.

- Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (tCMS) – a new and experimental approach, which to my knowledge has not quite made it out of the laboratory yet.

- Sensorimotor Retuning (SMR), as was first designed by Dr Victor Candia at the University of Konstanz about 15 years ago. This approach uses constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) to create conditions under which the dystonic musician can perform repetitive motions that will induce neuroplastic responses in the desired direction, i.e., to induce the re-separation of representational areas for each finger in a dystonic somatosensory cortex. CIMT, by the way, was first found to be effective in helping stroke victims recover lost motor functioning. Though effective and reliable, SMR as applied by Dr Candia was limited in its effect, in that it only normalised excessive activation in a dystonic hand. In the past year, I have used the same principles that guided Dr Candia to apply CIMT to dystonic musicians to design an addendum to the SMR program, which leads to a fully resolved, non-dystonic hand.

This, then, is essentially an overview of what dystonia is, how it can be developed and how it functions, and a quick look at what you can do about it. What I’d like you to take away from this tonight, more than anything is:

a. Focal hand dystonia for guitarists is a problem of learning, not a disease, or curse, or anything else…it’s an example of maladaptive neuroplasticity, whereby you essentially ‘learn your way into a corner’. Therefore, when people talk about recovering from dystonia, the word ‘cure’ is also not appropriate. Just as dystonia can be developed through actions over time, it can also be resolved.

b. I see that this doesn’t seem to be much of a problem in Thailand, going by the self-reportage we have of it here, but in the West, focal dystonia in musicians is very much a taboo subject, and is not spoken of. There seems to be a stigma associated with it, not unlike there is with mental health issues (not that that’s okay either). I suspect this has a lot to do with a lack of understanding of both its onset and resolution. I believe it’s important that we all, as musicians, do whatever we can to generate awareness of this being a part of living in the classical music industry or world – perhaps a small part, in terms of the number of people it touches, but a significant one nonetheless.

c. As more and more classical guitar scenes/cultures develop around the world, the incidence of focal hand dystonia in guitarists is probably going to go up, and Thailand today is a prime example of that – recall that lots of loud and fast playing at a high level is the number one predisposing factor. Competition culture, where young players often try really hard to perfect playing pieces that may be at the limit of their technical ability, doesn’t help at all. As teachers, it is incumbent on us to keep students developing holistically, and healthily. Key in all this is teaching young guitarists how to practice smartly, rather than for hours on end.

d. Dystonia, for all its serious implications for a musician’s career, is an occupational hazard (recall that Germany has even formally recognised this, as I told you earlier). It’s not irreversible, but its resolution through the application of the appropriate science is very recent, and not very well known. It’s important that people who have it know that behavioural therapy is a viable approach to resolving it.